Product Management Is Really Innovation Management

What is innovation? Innovation is not new.

Humans are creative by nature. Innovation is written into our DNA. We have our wits, not our strength or speed, to thank for the fact that we didn’t end up as just so much smooth-skinned lion food thousands of years ago.

When faced with challenges, we conceive innovative solutions that change the way we live our lives.

Driven by humanity’s intense need communicate, our ancestors innovated from pictures painted on cave walls to spoken language, then to written language, then from handwritten books to the printing press and newspapers, and on to radio and TV. The spiral of innovation has continued into the Internet age with the creation of electronic books, social media, and search engines that deliver information from all over the world at light speed.

Each step represented a significant improvement upon the previous solution.

Given that humans instinctively innovate, we have to ask the question, “Why do so many companies fail to do so?”

Innovation defined.

This definition is critical because the term is so often misused. Many organizational leaders use the word “innovation” simply to refer to anything new or different.

What is missing from this conception is that innovation is not simply change; it is change that creates value.

Daniel Scocco of the Innovation Zen blog writes, “The first confusion to dismiss is the difference between invention and innovation. The former refers to new concepts or products that derive from individual’s ideas or from scientific research. Innovation, on the other hand, represents the commercialization of the invention itself.”

From a business perspective, effective innovation changes the market by making possible the delivery of increased value to the customer, creating a competitive advantage for the organization.

Jim Andrew, author of Payback: Reaping the Rewards of Innovation, puts it more bluntly: Innovation is about making money.

Innovation occurs when:

- A currently unsolved problem is solved, fundamentally changing the way that things are done

- A new solution to a problem emerges that is significantly better than any previous solution, where “better” can be defined as faster, cheaper, easier to use, more reliable, etc.

Importantly, incremental improvements or feature enhancements devised to counter a capability from a competitor or to address a problem impacting product performance do NOT constitute meaningful innovation. This process does not result in significant leaps in product value.

Products logically step through a gestational period within the organization, followed by an introduction period in the marketplace. The natural arc of a product’s lifecycle is from growth to maturity to eventually decline.

Companies that innovate extend the lifecycle of a product, essentially creating loops back to earlier points in the arc. A genuinely better version of the product can mean a return from maturity back to a growth stage or from decline back to maturity. The introduction of broadband connectivity, for example, dramatically extended the lifecycle of Internet access delivery, forestalling the maturity of the product by over a decade.

Companies that fail to keep pace with innovation see their products and even their reason for being dissolve into irrelevance. A company selling only dial-up Internet access simply would not be in business today.

IBM CEO Samuel J. Palmisano comments on the need for innovation: “The way you will thrive in this environment is by innovating—innovating in technologies, innovating in strategies, innovating in organization model.”

Lafley and Charan, authors of The Game Changer, argue that innovation puts companies on the offensive. Through innovation, companies create a step change in value for the market, thereby surpassing competitive threats.

For innovation to yield rewards, innovation programs cannot simply be laboratories for testing and launching new ideas in the hope that one of them takes flight in the marketplace. Such an approach is a costly exercise, akin to a gambler paying the ante for one poker hand after another, waiting endlessly for the day when he is dealt a royal flush.

There must be a method for identifying lucrative opportunities and a process for execution. The goals of innovation and product management are inherently aligned. Product managers launch and support products in a dynamic, competitive marketplace. For a product to be successful, it must deliver value to its users, value that no competing alternative can match.

A product delivers value to users when it:

- addresses a need, solves a problem, or meets an end goal; AND

- is delivered at a price point that convinces buyers they have received a fair exchange for their money.

For a product to remain successful, it must continuously deliver unique value. Achieving this goal is not easy, as competitors constantly enter the market, giving buyers more choices at more prices. Profits therefore tend to be driven downwards over time. Product managers must always be searching for a competitive edge that they can exploit to combat this effect.

Strategic Product Management should therefore be defined as the delivery and maintenance of products that, within their target market:

- Deliver more value than the competition (user focus)

- Create a sustainable competitive difference (buyer focus)

- Generate ongoing benefit to the organization (organization focus)

Scott Berkum, author of The Myths of Innovation, deciphers why most companies are not innovating, noting that:

- Teams don’t trust one another and hence collaboration is nonexistent

- Managers are risk averse

- Innovation is hard work and takes time

According to Berkum, “The main barriers to innovation are simple cultural things we overlook because we like to believe we’re so advanced. But mostly, we’re not.”

Robert Tercek, an innovation consultant, has also pinpointed key reasons for failure. He states that, “The physical environment needs to be conducive to innovating. An office space similar to a rabbit warren will not inspire innovation teams to think creatively.”

Tercek observes that a second reason why innovation fails is that the innovation team often lacks the authority to bring ideas to completion.

Thirdly, innovation fails because those innovating may lack the necessary skills to “sell” new concepts.

Poor product management is a barrier to successful innovation.

From a product management perspective, organizations may struggle to innovate because their product management teams focus on day-to-day minutia, failing to prioritize activities that deliver new solutions to the market.

The entire structure of product management in these organizations runs contrary to the goal of innovation. Product managers cannot perform strategic tasks if they are constantly loaded down with operational and maintenance activities. They cannot discover and understand emerging customer needs and problems. They do not have the opportunity to engage in conversations, ask questions, or even simply observe their customers.

This scenario is a consistent product management problem across many industries. Far too many organizations see product management as a support function to sales, marketing, and engineering. But product management should lead an organization rather than serving it.

Effective product management leads innovation.

Ideas can emerge from anywhere within an organization. Quantitative market research, contextual enquiry, qualitative market observations, and customer visits or complaints can all spawn new ways of thinking.

Importantly, these ideas must be collated and channeled through a review process to determine which have merit. A persistent point of failure in innovation is the inability to sift through a large pool of ideas and identify the ones that are worthy of development.

In our opinion, all ideas should be fed into a product management framework to assess and distill them, leading to eventual action on only the strongest ideas, turning them into profitable products.

A recent Nielsen study (June 2010) of the FMCG industry showed that successful innovators have precise new product development processes:

FMCG companies with rigid stage gates—decision points in the process where a new product idea must pass certain criteria to proceed forward—average 130 percent more new product revenue than companies with loose processes.

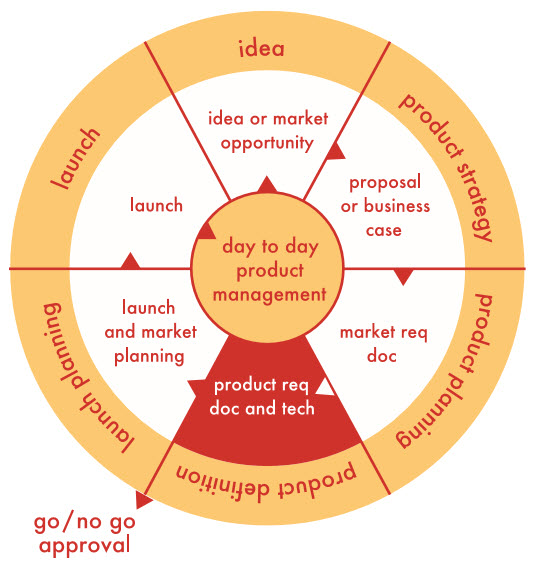

Idea Phase

During the ideation phase, product managers should use the market potential formula to:

- Filter ideas to find those worth pursuing

- Understand the financial rewards to be gained

To calculate the market potential for a product or service, determine the size of the market problem, the value of the problem to consumers, and the price or the duration over which consumers are willing to pay for the problem to be solved.

Product Strategy Phase

Once a promising idea has been identified, the next stage of the product delivery process involves elaborating on the idea, determining if the business has the capability to develop the idea, and refining projections of the financial return.

During the product strategy phase, the product manager should prepare:

- A more detailed proposal of the idea

- A business case to determine the idea’s capability to obtain some or all of the market potential, the costs of delivery, and the likely return on investment

No matter how creative an idea might be, if it will not deliver a return to the business, it is NOT an innovation and should be abandoned during this phase.

It is important to note that during the product strategy phase, the business case is conjectural, since the product idea is still in its infancy.

Product Planning Phase

During the product planning stage, the project management team further defines and assesses the target market’s need for the proposed idea. Seeing the idea through the eyes of a potential customer drives further crafting of the concept.

The product planning stage defines user requirements and sets the boundaries of the new product or service. A market requirements document is the resultant activity of this phase.

Product Definition Phase

During the product definition phase, product managers initiate one of the following activities in order to create a product requirements document that defines the features and functions of the product in detail:

- Develop an interactive, high fidelity prototype to test the product idea and to help finalize the requirements before development.

- Engage with a technical team to rapidly prototype the product idea and, consequently, discover and describe the rules governing creation of the product.

- Create low fidelity, paper mockups of the product to test the idea without exhausting technical resources, basing the product requirements document on the outcomes achieved with the mockups.

Activities within the product definition stage are NOT onerous. Without clear documentation of product requirements, an informed final go/no-go decision is impossible.

Final Words

At their cores, product management and innovation have the same goals. Both practices look to the market and to users for problems that are worth solving—problems that, when solved, will deliver value to the user and rewards for the business.

To be successful in achieving these goals, both product management and innovation require continuous effort, time, and a robust, repeatable process. If product management is effectively resourced and outwardly focused on understanding users and buyers in the marketplace, it can become a company’s engine room for innovation.

However, if product management is forced to focus on day-to-day operational activities, opportunities for innovation will seldom arise, and will be overlooked when they do.

Organizations that seek to deliver innovation to the market should therefore resource their product management teams to enable them to focus on emergent market opportunities and potentially disruptive market change.

About the Author

With almost twenty years of experience in program and product management, Rachel Everett has led and coordinated large product development efforts across a range of industries. Ms. Everett’s research focuses on customer-centric product design and development. She has written extensively on the topic and lectured at conferences and universities.